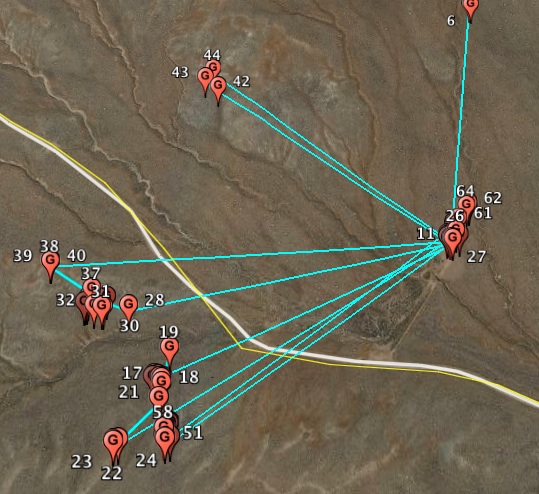

Our collaborator Jen Forbey came back for a second visit this year to get us oriented to measuring the habitat and sagebrush characteristics at sites used by our encounternet-tagged males.The process starts by downloading a male sage-grouse’s previous day’s gps locations. We throw the points onto Google Earth and look for areas the males were spending a lot of time (in other words, where several points are in within a few meters or 10′s of meters). During they day, presumably these points represent a patch where the male was foraging, and at night, likely a roost site. We load these points onto a hand-held GPS unit, then navigate to the site.

Once we are at the high-use area, we look around for sign of grouse (and always find something indicating a bird’s presence the previous day, usually some poop or a cecal cast). Once we know where a bird was actually standing, we look at nearby plants for bite marks indicating the grouse was browsing on the plant. We measure browsing intensity and dimensions of the plant themselves. We also use a couple of methods to measure ground cover- a Daubenmire frame where we measure rough abundance of grass and forbs in a small area, and also take a photo of a larger patch of ground from a camera suspended a set distance above the ground. Finally, we clip a few small branches from the sage-plant so Jen and her team can measure nutrients and toxins in the browsed and unbrowsed plants in the area.

When sage-grouse browse, they often leave parts of leaves. You can see the fresh browse marks (cut leaves with green centers) on the left and right of this photo.

Even more than we anticipated, this sage-sampling has been both illuminating and fun. There’s just something really neat about being able to walk a mile (or at least a kilometer) in the shoes of our birds, and see where they are spending time on the landscape. I feel like we are finally studying a complete bird, and not just the fraction of one that displays and fights on the lek. The process of the sampling itself has been enjoyable (at least in the relatively nice weather we’ve been having); it’s nice to be able to work outside with a team of people and to be able to talk without fear of scaring the birds.