We survived the pack-up and clean-up, and are back in Davis. Once again, Wyoming made this somewhat challenging. There’s been a long-standing joke with our local contacts that runs something like “winter isn’t over until the California ‘Chicken’ crew leaves.” This originated in our first few years, when we always seemed to leave town with a winter storm on our heels. This year, the weather gods seemed to want to revisit this joke. Our pack up week saw 2 decent storms roll through Fremont County. Neither left insurmountable amounts of snow, but we ended up having to pack everything up in a cold muddy morass. Adding to the list of why field work is not always glamorous: scrubbing out dirty trashcans in 32 degree weather with a driving snow, and laying on ones back in a mud-puddle to secure a tarp around a lumber pile. The late season storm did provide some opportunities though, such as seeing the now-blooming paintbrush poke through the snow.

We had a break in the weather on our final weekend, and traveled with Stan to Oregon Buttes, a scenic and historic area south of South Pass. Turning south of the highway between Farson and Lander, the first stop was a marker for the Oregon Trail, which comes through that (relatively) low and flat region of the Continental Divide. Onward and we come near the Oregon Buttes themselves, which we got to view through weather oscillating rapidly between snow, clouds, and sun.

Finally we worked our way towards the badlands area of Honeycomb Buttes. The flatlands approaching the buttes held almost comically picturesque herds of wild horses.

The rockhounds among our group (everyone) collected beautiful pieces of petrified wood, fossilized algae, and agates. Finally onto the badlands, which were sprinkled with shards of fossilized turtle shell. It was a fantastic day to explore some different sage-grouse habitat and see a new part of the local scenery.

The drive back was uneventful. We made it to Elko, NV as our halfway point, and bypassed the Cabela’s superstore in Reno in the interest of beating Sacramento rush-hour traffic.

Looking back on the 2014 field season, how did it go? It was a particularly exhausting season, with so many new things to figure out, and a large crew to manage. In some ways it felt like our first season when everything was new, although with the pressure and expectations that come with a lot of goals and the knowledge that we are mid-grant with limited time to accomplish our objectives.

That said, I think we kicked butt this year. We crossed off several major items in our 2014 field effort. First off- the robot experiments were a real success. Anna did a wonderful job in planning these out, and the birds and weather generally cooperated. We had two target areas on each lek, and were able to run at least 3 different trials at each one. On some days both Gail and I piloted robots at the different leks- a first for us (and the first time I’d gotten to drive during a real experiment). Anna was able to train James to be a second experiment director for these dual-experiment days. Hopefully our data will allow us to look both for seasonal trends in courtship effort as well as differences individual male persistence. We will only know the results once we analyze the video and audio data collected along with the experiment, but our impression was that everything worked pretty well this year.

Secondly, we accomplished a whole suite of interrelated objectives as part of the encounternet tag work. Step one of this was to actually capture birds and get tags on them. Frank and Julia got up to speed on this really quickly, and we ended up catching close to 30 birds. Not sure what our average was, but I’d guess close to two birds per night which is not bad with for the relatively small crew we had available to go catch birds on a given evening. Getting the harnesses on the birds had stymied us in the past, but this season we got the hang of it (the rump mounts are a little tricky to fit, and will fall off pretty much immediately if they aren’t attached properly).

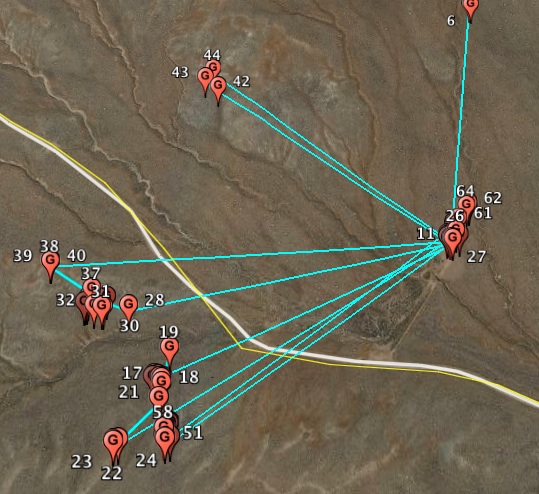

With tags on birds, we were ready to tackle the encounternet system itself. With some trial and error and updated versions of the firmware supplied by John Burt, we managed to work on power management of the tag and positioning of the receiving basestations. We ended up with four males for which we could get hourly GPS fixes along with accelerometer activity samples coincident with those fixes. Much thanks to Sean and Sam for building some of the antenna mounts we used.

Finally, with the GPS data flowing in, we could start to crack the foraging ecology questions. Julia was instrumental setting getting an easy protocol for moving the GPS data from our Google Earth plots onto our GPS. The tags seemed very reliable in pointing us to areas heavily used by the birds, and with Jen Forbey’s help, we became adept at taking samples of the sage and making quick assessments of the habitat at the activity site. We also did lek-based assessments to measure foraging quality at areas surrounding 6 of our leks.

These were the main goals, but we also tackled some auxiliary projects this year. In conjunction with the sage-sampling work, we looked took a series of photographs of various sage-grouse sign (browse marks and poop) to look at how it aged over a period of days. This will help assure us we can identify very recent grouse activity from older sign.  Second, we tackled the buttprint aging project again- Sam got started on this early in the season and so this year we’ve managed to save multiple photos for a number of individuals. Combining last year’s data, hopefully we can answer whether it’s possible to reliably age second-year birds based on a distant picture of their tail, and whether this is easier to do early or late in the season.

Second, we tackled the buttprint aging project again- Sam got started on this early in the season and so this year we’ve managed to save multiple photos for a number of individuals. Combining last year’s data, hopefully we can answer whether it’s possible to reliably age second-year birds based on a distant picture of their tail, and whether this is easier to do early or late in the season.

We accomplished all of these research goals while developing a completely new workflow for our video data. This year we made the transition away from tape cameras and recorded all of our video in full digital format on SD cards.

All in all, a very productive year! Many thanks again to our crew for all their hard work this season!