It’s now official- I’ll be co-teaching a course during the first summer session this year. The course is NPB 102, Animal Behavior (in the department of Neurobiology, Physiology, and Behavior). I’ve given a guest lecture in this class before, and I’m pretty excited to get to lead the class.

Tag Archives: UC Davis

Undergraduate Research Opportunties

Now that we’re back from our field research on the sage-grouse in Wyoming, we are turning our attention to the rest of the year in Davis. Towards that end, we would like to invite motivated students to join our lab this summer to participate in our research. These projects would involve measuring behaviors of male and female sage-grouse using videos of courtship interactions on the lek. Other projects may involve analyzing vocalizations using multichannel sound recordings we collected this spring. Either way, it’s a good chance enjoy some Storer Hall air conditioning while participating in exciting projects.

If you are interested, email me, and I can provide more information. The next step would be to attend an information session to answer your questions. We hope to have one or more of these within the next week or two.

For more information, please see the links provided at the top of the “Undergraduate Research Page”

Undergraduate Research Conference Participants

A brief (and tardy) note of congratulations to two of the students in our lab – Tawny and Marty, who both presented at this year’s Undergraduate Research Conference. Tawny is working on a senior practicum, and has been investigating lateral biases in aggressive behaviors in the sage-grouse. Marty came in last summer through a special research program (the FASTRAC program), and has been looking at male responses to robot females presenting either interested or disinterested behaviors.

You can check out an article about it here. Gail and Tawny were both interviewed for this article!

Sage-Grouse leks: One of the greatest shows on Earth!

I’m kicking off my blog for the 2013 research season with a brief description of what makes sage-grouse such a great bird to study for someone interested in animal behavior and evolutionary biology.

One of North America’s most spectacular birds is also a species that not many people have seen. I’m referring to sage-grouse: I study the more widely distributed greater sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus); I have yet to personally see the less common Gunnison’s sage-grouse (Centrocercus minimus), but that is definitely on my wish list. Given the spectacular plumage of a male sage-grouse in display, why are these birds so hard to see? A quick look at a female sage-grouse tells you the girls are built for crypsis- well adapted to blending in with their environment. For most of the year male sage-grouse also play the hiding game, so unless scared into flight they may pass unnoticed. Yet for a couple of months in winter and spring, males come into their traditional display grounds (called leks, from a Swedish word for “child’s play”) and put on one of the greatest shows on earth. These leks are often in fairly remote areas, and males typically attend them only in the early morning hours. Both of these reasons help explain why getting a look at this spectacle can be a bit of a challenge.

These unusual breeding clusters have captivated not only birders but evolutionary biologists as well. In about 90% of birds, both parents provide some care for the nestlings. In those cases, females are often choosing their mates at least partly on the material benefits they get from this partnership, whether it be the quality of the male’s territory or his ability to provision the female during incubation or the chicks once they’ve hatched. [Note- in many birds males and females mate outside of this pair bond, but that is a tale for another day]. Lekking species are therefore unusual among birds in that males don’t form a bond with their mate nor provide any child care. Scientists are still trying to unravel some of the puzzles that leks represent. Why do males cluster together to display, rather than searching around for females, following females around, or spacing themselves farther apart and defending larger territories like most other birds do? If males aren’t helping raise the kids, why are females so picky? What benefits do females get from choosing one male instead of another? And given that females often pick only a few among the many males on a lek, why do the “loser” males bother to stick around?

(This is a 3-hour time lapse video of the lek. The males appear as small black-and-white specks at the bottom of the frame)

Lekking animals also tend to be high on the charisma scale. Besides the spectacular sage-grouse and their cousins the prairie chickens and sharp-tailed grouse, other lek-breeders include some of the most beautiful and acrobatic birds out there, including birds of paradise, neotropical manakins, peacocks, cock-of-the-rock, some hummingbirds, and ruffs. When we see a species in which males are larger or more colorful than females, we presume these differences are related to an evolutionary process called sexual selection, where one sex- often the males- competes either directly for access to females or indirectly by producing the best advertisement among the other males. This certainly seems plausible for sage-grouse; not only are adult males almost twice the weight of females, but they have a range of specialized feathers, brightened skin patches, and other unique structures.

The distinctive air-filled vocal sacs are actually part of the digestive system; once inflated with air, powerful muscles just under the skin help move and shape the them during display. In spite of decades of research and routine collection by hunters, we are still finding surprising structures in these birds. Just recently we discovered that male sage-grouse have an almost songbird-like syrinx (sound-producing organ analagous to the human larynx) capable of producing two tones at once. All of this adds up to the bizarre appearance of the male that has presumably evolved through sexual selection- the males with the more elaborate versions of these unique features get to mate with more females and pass on more copies of their genes to the next generation.

These differences between males and females extend to courtship behaviors as well; males and only males have a characteristic “strut” display. A male’s strut serves to attract females to the lek from across the landscape, to woo females once they are on the lek, and most likely to help claim their small patch in the midst of all the other males. Each display lasts about two seconds and involves coordinated movements of the wings and body.

For sage-grouse, courtship is not just a visual spectacle. Males produce a variety of sounds during the strut display. The first two notes actually are not vocalizations at all, but instead made by rubbing stiff, pointed breast feathers against the inside of the wings. This is somewhat analogous to how crickets chirp. Making sounds with feathers may sound unusual, but it has evolved repeatedly in birds. Some common species in the Bay Area that do this include Mourning Doves (the ‘wee-wee-wee-wee’ made during take off) and Anna’s Hummingbirds (the loud chirp made at the nadir of the male’s dive display).

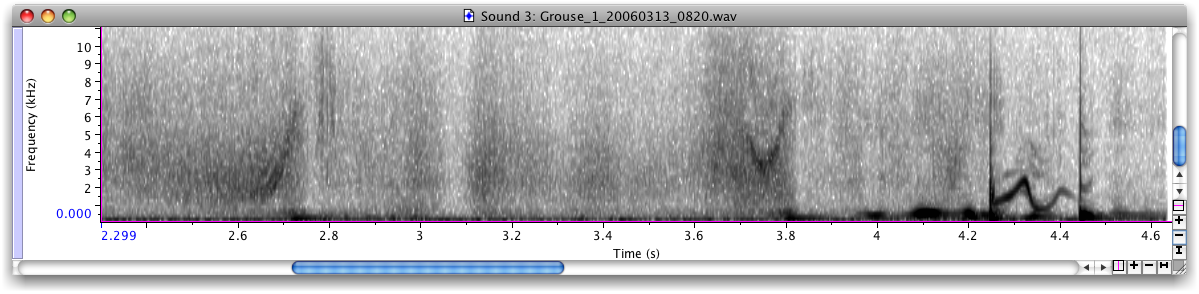

Spectrogram of a sage-grouse display. The two feather-produced 'swish' notes occur at about 2.6 and 3.6 seconds. The first low frequency 'coo' note is at 4 seconds, and is followed by the pop-whistle-pop at about 4.3 seconds. You can hear this in the video above.

The remaining notes are true vocalizations made by the syrinx, although unlike most birds they are made with the beak closed. These sounds start with a series of three low frequency ‘coo’ notes, and conclude with an up-down-up ‘whistle’ note sandwiched between two staccato ‘pops’. You can see these in the spectrogram- this is a visual representation of sound and you can read it much like reading music, with time progressing towards the right, pitch becoming higher towards the top of the figure, and the darkness representing something like loudness. Females may care about some very subtle differences in these sounds when they are looking for a high quality mate. Researchers have compared sound recordings of successful and unsuccessful males and found differences in the relative timing of the two ‘pop’ notes, and maybe the loudness of the whistle. What is amazing is that the differences between ‘Mr. Right’ and ‘Mr. Wrong’ are on the order of less than a tenth of a second. Females may have quite the ear when it comes to picking their mate!

That’s a quick introduction to sage-grouse in the spring. I feel extremely lucky to have heard and seen this show for the past several years as part of my research at the University of California, Davis. Along with Professor Gail Particelli, graduate student Anna Perry, and our intrepid field crew, we will be conducting research into several aspects of sage-grouse behavior and ecology from our field site just east of the Wind River Range in Wyoming. Over the next couple of months I’ll be discussing what it takes to set up a camp like this, how we use new technologies (including robotic birds!) to study courtship in this species, and review some of the conservation studies out of our lab. I hope you’ll join me for our 2013 field season!

Re-posting Field Crew Advertisement

For a variety of reasons including wanting to expand the size of our crew, we are looking for an additional one or two assistants for our rapidly approaching field season. Dates potentially a little flexible, but we really need people comfortable driving an ATV (even better if received agency training or certification). Feel free to contact me with any questions.

For a variety of reasons including wanting to expand the size of our crew, we are looking for an additional one or two assistants for our rapidly approaching field season. Dates potentially a little flexible, but we really need people comfortable driving an ATV (even better if received agency training or certification). Feel free to contact me with any questions.

Anyway, here’s the revised advertisement:

FIELD ASSISTANTS (1-2) needed approximately March 3 – May 5 (dates potentially flexible) for investigations of the behavior and ecology of Greater Sage-Grouse near Lander, Wyoming and the scenic Wind River Range. The projects are part of a larger effort in Prof. Gail Patricelli’s lab at UC Davis to understand how sexual selection shapes sage-grouse display behaviors- see the following websites for more information (http://www.eve.ucdavis.edu/gpatricelli/) and (http://www.alankrakauer.org). Assistants will use video and audio recording technology to support an NSF-funded study of courtship dynamics and display plasticity on the lek. Duties include maintaining camera and acoustic monitoring equipment, observation of basic courtship behavior and lek counts, GPS surveying, habitat characterization, assisting in the capture of adult sage-grouse, data entry, and some computer and video analysis. Assistants must be flexible in their needs and comfortable living and working in close quarters in a remote field station, and able to work in adverse field conditions (mainly MUD and COLD). Work will be daily and primarily early in the morning, with afternoon and night work required as well. Applicants must have a valid driver’s license, basic computer skills, ATV experience (ideally with formal safety training or certification), and have succeeded in at least one field biology project in the past. Wilderness First Aid or First Responder, and prior experience spotlighting for sage-grouse, preferred but not required. Must be able to show proof of United States employment eligibility. Assistants will receive $600/mo plus room and board, but need to provide their own transportation to Lander and their own personal gear. Please send a cover letter, resume, and contact info (email and phone) for two (2) references to: Alan Krakauer, Department of Evolution and Ecology, University of California Davis, One Shields Avenue, 2320 Storer Hall, Davis, CA 95616, or preferably by email to ahkrakauer [at] ucdavis.edu. The positions will remain open until filled, and review of applications will begin immediately.